This section presents the replies to the Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) about the Water Convention. Over 50 questions are grouped upon seven thematic areas. The FAQs are also available as a publication.

- 1. ADDED VALUE AT GLOBAL, TRANSBOUNDARY AND NATIONAL SCALES

-

1.1 What is the relevance of the Water Convention for the achievement of the Sustainable Development Goals?

The Convention on the Protection and Use of Transboundary Watercourses and International Lakes (Water Convention) is an important tool to operationalize the achievement of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development and its Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) , particularly with regard to water and transboundary water cooperation.

The Water Convention facilitates the achievement of Goal 6 (clean water and sanitation) through its integrated and intersectoral approach and its attention to the prevention and reduction of water pollution, the conservation and restoration of ecosystems, and water use efficiency. As sixty per cent of global freshwater flow comes from transboundary basins, the Convention provides the legal framework and cooperation mechanisms to ensure for the timely and sufficient availability of water of adequate quality for humans, economies and ecosystems. It directly supports the implementation of SDG target 6.5, which requests that all countries, “[b]y 2030, implement integrated water resources management at all levels, including through transboundary cooperation as appropriate”.

The work under the Water Convention is also relevant in supporting the achievement of other SDGs:

• Goal 2 (zero hunger), Goal 7 (affordable and clean energy) and Goal 15 (life on land) through, for instance, the Convention’s integrated approach to the development of sectoral policies and its activities on the water-food-energy-ecosystems nexus.

• Goal 3 (good health and well-being) through the Convention’s activities in cooperation with the Protocol on Water and Health.

• Target 11.5 (reducing the impact of disasters, particularly water-related disasters) and Goal 13 (climate action) through the Convention’s activities on water and climate change.

• Goal 16 (peace, justice and strong institutions) and Goal 17 (partnerships for the goals) through the Convention’s activities on integrated water resources management (IWRM) and partnerships for transboundary water cooperation.

In addition, UNECE together with UNESCO, are custodian agencies for SDG indicator 6.5.2 (Proportion of transboundary basin area with an operational arrangement for water cooperation), which measures the progress in transboundary water cooperation worldwide. As the reporting on SDG indicator 6.5.2 is closely linked with the reporting under the Convention, the Convention also offers a framework to discuss global progress on transboundary water cooperation and to identify common challenges and define responses.

Additional resources:

• Progress on Transboundary Water Cooperation. Global baseline for SDG indicator 6.5.2 (2018). UN-Water, UNECE, UNESCO.

• Reporting under the Water Convention and SDG indicator 6.5.2.1.2 What are the advantages and benefits for countries to accede to the Water Convention?

By becoming a Party to the Water Convention, a country joins the international legal and institutional framework of the Convention that has already proven its effectiveness over the past two decades. This means that a country can use the instrument that has successfully facilitated the development of many transboundary water agreements and joint bodies and led to concrete results on the ground, including improved water quality, mitigation of the impacts of floods and droughts, improved joint planning in many areas (e.g. adaptation to climate change, management of dams and reservoirs, etc.), and better human and ecosystem health.

The Global Opening of the 1992 Water Convention (ECE/MP.WAT/43/Rev.1) Guide to Implementing the Water Convention (ECE/MP.WAT/39), paras 21-42

Overall, participation in the Convention—namely adherence to its rules and cooperation through the intergovernmental platform of the Convention—increases certainty and predictability in relations between riparian States and thus helps prevent potential tensions and differences, contributing to the maintenance of international and regional peace and security.

By becoming a Party, a State signals to other countries, international organizations, financial institutions and other actors its willingness to cooperate on the basis of the norms and standards of the Convention. Accordingly, such a State would enhance its respect by other actors in the international community for adhering to the rules and standards of the Convention.

A Party to the Water Convention benefits from the existing experience under the Convention, e.g. its guidance documents, activities and projects on the ground. The institutional mechanism of the Convention also provides support to the Parties in concluding specific transboundary water agreements and in setting up joint bodies or strengthening existing ones. This is particularly valuable in those basins where difficulties to conclude agreements exist.

Accession to the Water Convention can also facilitate the financing of water management and transboundary water cooperation, both from national sources as well as from international donors.

When becoming a Party, a country can participate in and contribute to the Water Convention’s institutional structure and decision-making, fostering the implementation of the Convention and its further development. Parties can decide on the development of the Convention, be elected to the Convention’s governing bodies and lead activities under the Convention. Parties can also participate in the development of the Convention’s three-year programme of work so that it can better respond to their specific needs. Parties can also make use of the Convention’s Implementation Committee that is available to assist in finding solutions to complicated water management issues and to help overcome difficulties in transboundary cooperation.

Furthermore, Parties to the Water Convention collectively decide on the development of the Convention’s regime. They can initiate the negotiation of new legally binding instruments such as protocols or amendments to the Convention. They can elaborate new soft law instruments, such as guidelines or recommendations. They can establish new bodies within the Convention’s institutional framework. In this way, Parties can directly influence the further development of the Convention and international water law.

Participation in and implementation of the obligations of the Water Convention also improves water resources management and water governance at the national level. The Convention’s standards to be applied by all Parties, for example on the prevention, control and reduction of pollution at source, permitting, prior licensing of wastewater discharges, the application of biological treatment or equivalent processes to municipal wastewater, or the application of the ecosystem approach, can enhance national systems for water resources management and protection, especially if a Party develops an implementation plan and regularly reviews its efforts in implementing the Convention.

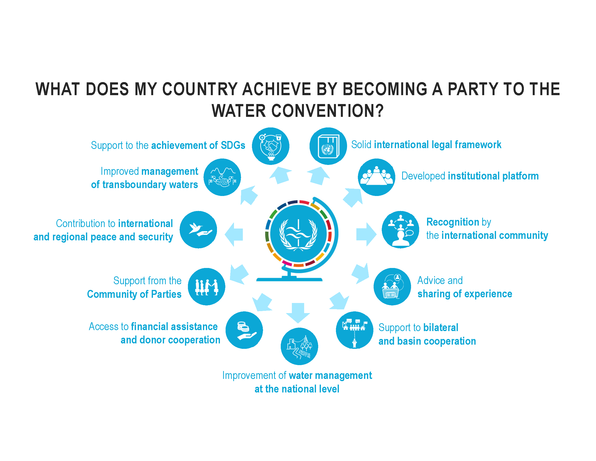

Last but not least, there may be additional advantages from accession for countries interested in one or an other area of work under the Convention. For example, a State suffering from frequent floods would benefit from the Convention’s activities on transboundary flood management and on climate change adaptation. The Figure below describes key benefits from participation in the Water Convention.

Additional resources:

1.3 What is the added value of accession to the Water Convention for a country that already has agreements and good cooperation with its neighbours?

Cooperation is an evolving process. By becoming a Party to the Water Convention, countries that already have agreements and good cooperation with their neighbours can learn about approaches, tools and experiences from other transboundary basins, which can strengthen cooperation in the basins they share.

Through the regular reporting mechanism under the Convention, and in particular through the efforts of countries sharing transboundary basins to coordinate their responses during the preparation of reports, countries can review their national capacity and identify areas to further improve transboundary water cooperation, including the possible need to amend their existing agreements, as appropriate.

While the obligation to conclude specific agreements for transboundary basins is indeed one of the key obligations under the Water Convention, cooperation under the Convention is not limited to specific agreements and involves many other aspects and issues. Parties regularly discuss and address new and emerging issues and embark on new tasks such as the development of soft law tools or the preparation of innovative assessments that pave the way for new potential areas of work and cooperation. For example, already in 2006, Parties to the Water Convention began working on climate change adaptation in transboundary basins —an emerging area of work at that time.

Since 2018, the financing of transboundary cooperation —another pressing common challenge—continues to be addressed in the framework of the Convention’s institutional platform. In other words, Parties that already have agreements and good cooperation with their neighbours have many more opportunities to work on issues that can reinforce transboundary water cooperation in the basins they share, even when it functions well.1.4 What is the added value of accession to the Water Convention for a country whose neighbours are not Parties to the Water Convention?

Accession to the Water Convention demonstrates a country’s commitment to act in accordance with international water law and to advance transboundary water cooperation based on the principles, norms and standards of the Convention. Such a step sends a positive signal to neighbouring countries, the international community and to donors. Accession not only provides a country with the argumentation to strengthen cooperation in the transboundary basins it shares, it also sets an example to other countries in the shared basin and may help them decide on acceding to the Water Convention. For example, the Water Convention provided the reference for negotiating the 2001 Framework Agreement on the Sava River Basin at a time when only two of the four riparian countries were Parties to the Convention; a few years later, all four riparian countries of the Sava River Basin became Parties to the Convention.

Nevertheless, a Party to the Convention is not legally bound to implement the Convention in its relations with riparian countries that are not Parties to the Convention.

The immediate benefits of accession to the Water Convention for a country whose neighbours are not Parties lie in two key domains:

• The first category of benefits relates to the improvement of water resources management at the domestic level. Accession to the Convention presents an occasion to review and strengthen national water policies and practices, enhance intersectoral cooperation and stakeholder participation in water resources management, and introduce new preventive measures at the national level for the optimal utilization and protection of transboundary waters and related ecosystems. In other words, accession can prompt a re-boost of domestic water management and governance frameworks and thus improve the status of water bodies within the national borders and beyond. For example, accession to the Water Convention in 2012 prompted Turkmenistan to develop and adopt a new Water Code (2016) in which integrated water resources management and the basin approach were introduced.

• The second category of benefits results from the participation of Parties in the Convention’s institutional structure, which includes access to advice and the sharing of experiences within the framework of the Convention’s institutional platform. Such support may include assistance in establishing cooperation between Parties and non-Parties to the Convention.1.5 What are the benefits of accession to the Water Convention for an upstream country?

The Water Convention encompasses the rights and obligations for both upstream and downstream countries and does not differentiate whether the country is upstream or downstream. The Convention is firmly based on the principles of equality and reciprocity. This is why Parties to the Convention are both upstream and downstream countries.

Upstream countries can be vulnerable to transboundary impacts (e.g. deterioration of spawning conditions upstream due to the operation of infrastructure or overfishing downstream). Cooperation between riparian countries in the form of bilateral or multilateral agreements and joint bodies, required under the Water Convention, allows upstream countries, as much as downstream ones, to address their issues of concern.

Through cooperation in the form of agreements and joint bodies, required under the Convention, both upstream and downstream countries can reduce economic costs by implementing joint measures and activities (e.g. climate change adaptation measures, joint flood management or joint management of water infrastructure like dams) and promote regional integration and improved access to the sea. They can access knowledge and expertise which is available in other riparian states. They can also benefit from participating in joint efforts of riparian states aimed at the development of basin management plans or basin-level programmes (on floods or protected area management) and tools (GIS mapping, climate change modelling, etc.). A good example of such cooperation is the 70-year-old cooperation of the riparian countries in the framework of the International Commission for the Protection of the Rhine (ICPR) , which brought benefits to both upstream and downstream countries, including the restoration of fish migration upstream. Another example is the cooperation under the 2000 Agreement on the Use of Water Management Facilities of Intergovernmental Status on the Rivers Chu and Talas where both upstream Kyrgyzstan and downstream Kazakhstan enjoy benefits, with Kazakhstan financially contributing towards the maintenance of water infrastructure located in Kyrgyzstan and used by both countries.

In addition, transboundary water cooperation may bring indirect benefits to upstream countries in areas beyond the water sector, resulting in increased trade, investment, economic integration and access to technology.

Additional resources:

• Policy Guidance Note on the Benefits of Transboundary Water Cooperation: Identification, Assessment and Communication (ECE/MP.WAT/47).1.6 Do downstream countries enjoy only rights and have no obligations under the Water Convention?

Downstream countries are bound by obligations of the Water Convention as much as upstream countries. This is so because many transboundary impacts from measures taken downstream can be transferred upstream (e.g. impacts related to fish migration, invasive species, poor management of sedimentation/siltation). Furthermore, only together can Parties progress towards the implementation of the core obligation of the Convention, which is to protect the environment influenced by their transboundary waters, including the marine environment.

The Water Convention is firmly based on the principles of equality and reciprocity and does not differentiate the rights and obligations of Riparian Parties based on whether they are located upstream or downstream. Its obligations, including holding consultations or informing of any critical situation that may have a transboundary impact, apply to both upstream and downstream countries. Downstream countries cannot distance themselves from the obligations set forth by the Convention on all Parties. For example, a downstream Riparian Party may not refuse to provide information upon request or exchange data with an upstream Riparian Party on the assumption of their irrelevance for the upstream Party.

Additional resources:

• Guide to Implementing the Water Convention (ECE/MP.WAT/39), paras. 290, 301, 319.1.7 Would the Water Convention be useful to every country, taking into account regional specificities and each country’s unique situation?

The Water Convention is a framework instrument designed on the understanding that every country and every basin is unique. Consequently, it stipulates general obligations of Parties and, at the same time, it affords flexibility so that Parties can best implement these obligations within their specific circumstances. In particular, the Convention requires Parties to develop basin-specific agreements, which should be adapted to local circumstances. Furthermore, many of the Convention’s obligations are of a due diligence nature, meaning that measures to implement them should be commensurate to the capacity of the Party concerned and its level of economic development.

The “umbrella” nature of the Convention, manifested in its institutional framework, within which the Parties cooperate, exchange information, collectively provide technical and legal assistance and further develop the provisions of the Convention, allows individual countries to benefit from participation in this framework instrument according to their specific situations and needs.

The Water Convention is therefore useful to every country with shared transboundary waters that is looking for a cooperative framework to support its efforts in strengthening cooperation with its riparian neighbours and the advancement of transboundary water cooperation worldwide. Many basin-specific agreements mention the Water Convention in their preambular paragraphs as forming an important basis, followed by provisions based on the text of the Convention but adapted to the specific circumstances in the basin concerned.

Additional resources:

• Tanzi, Atilla, Alexandros Kolliopoulos and Natalia Nikiforova (2015). Normative Features of the UNECE Water Convention. In: The UNECE Convention on the Protection and Use of Transboundary Watercourses and International Lakes. Its Contribution to International Water Cooperation. Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill | Nijhoff, pp. 116–129.1.8 Does the Water Convention hinder economic development?

The Water Convention does not hinder economic development. In fact, the economic situation observed in many Parties to the Water Convention has gradually improved. For example, between 2006–2009, Albania, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Bulgaria and Kazakhstan (Parties to the Convention at the time) have improved their status from lower-middle-income economies to upper-middle-income economies, according to the World Bank classification for respective years . In addition, between 2006–2012, Croatia, Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland and Slovak Republic (also Parties to the Convention at the time) have improved their status from upper-middle-income economies to high-income countries. While these positive trends are the result of many policies and multiple factors, which go well beyond the Water Convention, they do show that Parties to the Water Convention have seen their level of economic development increase.

Multilateral financial institutions and bilateral donors strongly value the participation of countries in multilateral agreements such as the Water Convention, and thus being a Party to the Water Convention facilitates investment in support of development projects. The existence of bilateral or multilateral agreements, as well as the creation of joint bodies for transboundary water cooperation in specific basins, are mechanisms that reduce tension and can facilitate agreement on development projects for which financing from financial institutions and bilateral donors may be requested. The World Bank’s approach, governed by the Operational Policy (OP)/Bank Procedure (BP) 7.50: Projects on International Waterways (2001) , recognizes that the cooperation and goodwill of riparian countries is essential for the efficient use and protection of the waterway. Participation in the Water Convention and compliance with its provisions serve as clear evidence of the willingness of riparian countries to cooperate and thus enhance the eligibility for international funding.

With regard to development-related infrastructure, the Water Convention provides clear and cooperative mechanisms in order to reach better informed decisions on the development of new infrastructure and to prevent related disputes and differences. The Convention builds on the key principles of international water law such as equitable and reasonable utilization, the prevention of significant harm, and the obligation of cooperation, which fully apply to the construction of new infrastructure and the operation and maintenance of existing ones. The obligation of Riparian Parties to hold consultations at the request of any Riparian Party regarding any issue covered by the provisions of the Convention includes, among others, consultations on infrastructure related planned measures.

The methodology for assessing benefits of transboundary water cooperation developed under the Water Convention enables interested countries to look into the wide range of economic, social and environmental benefits that have already been realized and that are potentially available in specific basins. Basin-specific assessments conducted in several regions have shown a wide range of benefits from transboundary water cooperation which are directly contributing to economic growth. These may include increases in joint investments, an expansion of the tourism sector, increases in energy security, agricultural productivity, regional trade and commerce, investments in research, and reduced costs of disaster prevention and preparedness.

See also the replies to the related questions:

Would the Water Convention be an efficient instrument for developing countries? [2.6]

Can a country accede to the Water Convention if it cannot implement all its requirements due to the lack of resources and capacity?[6.1]

Additional resources:

• Guide to Implementing the Water Convention (ECE/MP.WAT/39), paras. 36–37, 41–42.

• Policy Guidance Note on the Benefits of Transboundary Water Cooperation: Identification, Assessment and Communication (ECE/MP.WAT/47).

• Identifying, assessing and communicating the benefits of transboundary water cooperation: Lessons learned and recommendations (ECE/MP.WAT/NONE/11).1.9 How can the Water Convention prevent conflicts and wars over transboundary waters?

The obligations of Riparian Parties to the Water Convention, particularly the duty to cooperate and the obligations to hold consultations, exchange information, conclude agreements and establish joint bodies, are essentially aimed at and instrumental in preventing conflicts and wars over transboundary waters because they determine the day-to-day cooperation of Riparian Parties by setting certain standards for their behaviour and communication. Countries that have concluded agreements and/or established joint bodies may have disagreements over the management of shared waters, but they are less likely to enter into conflict or a war over transboundary waters.

Riparian Parties that have not concluded agreements and/or established joint bodies may be assisted by the Convention’s institutional framework in taking these steps, which will ultimately contribute towards strengthened cooperation frameworks in the basins concerned. Furthermore, joint activities often implemented by countries under the Convention’s framework (e.g. projects to set up joint monitoring or to develop a joint vulnerability assessment for a basin) contribute to increasing trust and understanding among riparian countries.

Last but not least, Parties that are facing difficulties in the implementation of the Convention’s provisions in a particular basin may address, unilaterally or jointly, the Implementation Committee under the Water Convention to ask for advice and assistance in improving the implementation of the Convention and in preventing potential conflicts at an early stage. An advisory procedure under the Implementation Committee is best tailored to accommodate such cases.

See also the reply to the related question:

What is the role of the Implementation Committee under the Water Convention?[6.5]1.10 How can the Water Convention contribute to the resolution of latent conflicts over transboundary waters?

The Water Convention can contribute to the resolution of latent conflicts by supporting the riparian countries concerned in taking steps towards cooperation on the basis of the legal principles of the Convention. This can be done, for example, through a technical project in the framework of the Convention’s programme of work to initiate steps towards cooperation. Such steps can take the form of meetings of technical experts or meetings devoted to a specific issue of common interest (e.g. flood protection). Organized under the aegis of the Convention, such meetings provide a neutral platform for dialogue between riparian countries. With time, they allow to build trust and a mutual understanding of the opportunities and benefits of cooperation.

In addition, the Implementation Committee under the Water Convention can be approached by Parties to the Convention to help resolve latent conflicts. Members of the Committee are outstanding lawyers and technical experts on water issues, and they can provide authoritative advice and mediation in complicated situations, including assistance in taking steps towards the negotiation of transboundary water agreements.

See also the reply to the related question:

What is the role of the Implementation Committee under the Water Convention?[6.5]1.11 How does the Water Convention promote integrated water resources management?

The Water Convention offers an operational framework to implement integrated water resources management (IWRM) in practice at both national and transboundary level. The Convention promotes a holistic approach, which takes into account the complex interrelationship between the hydrological cycle, land, flora and fauna based on the understanding that water resources are an integral part of the ecosystem. Furthermore, the Convention promotes the basin approach through the obligation to enter into agreements and establish joint bodies.

Cooperation under the Water Convention requires the involvement of different sectors of the central administrations of the Parties and their relevant local authorities, other public and private stakeholders, and NGOs. Such cooperation ultimately enhances the national capacity for water management. The sustainable use of water resources, including the protection of ecosystems and the integration of climate change aspects in the water resources management and planning, are other aspects of the IWRM approach that are promoted under the Convention.

The programme of work of the Water Convention for 2019–2021 specifically supports the implementation of IWRM, with three important sub-areas of work. The first sub-area is to develop a handbook on transboundary water allocation as both a tool and a source of information for the equitable and sustainable allocation of water in a transboundary context. The second sub-area, on the water-food-energy-ecosystems nexus , supports intersectoral dialogue and assessments through the application of the nexus approach to foster transboundary cooperation. The third sub-area concerns the EU Water Initiative (EUWI) National Policy Dialogues (NPDs) implemented by UNECE and the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) to provide expert and technical assistance in introducing IWRM in the countries of Eastern Europe, the Caucasus and Central Asia.

Additional resources:

• Water Convention Programme of Work 2019–2021 (ECE/MP.WAT/NONE/14).

• Methodology for assessing the water-food-energy-ecosystems nexus in transboundary basins and experiences from its application: synthesis (ECE/MP.WAT/55).

• A nexus approach to transboundary cooperation: The experience of the Water Convention (ECE/MP.WAT/NONE/12).

• Water Policy Reforms in Eastern Europe, the Caucasus and Central Asia. Achievements of the European Union Water Initiative, 2006–16.

• Implementation of the Basin Management Principle in Eastern Europe, the Caucasus and Central Asia. European Union Water Initiative National Policy Dialogues Progress Report 2016.

• Integrated Water Resources Management in Eastern Europe, the Caucasus and Central Asia. European Union Water Initiative National Policy Dialogues progress report 20131.12 Does the Water Convention reflect customary international law? If yes, what is the benefit of accession?

The Water Convention is based on and fully in line with customary international law. Its three-pillar normative structure includes: i) the obligation to prevent, control and reduce significant transboundary impact (the so called “no-harm rule”); ii) the equitable and reasonable utilization principle; and iii) the principle of cooperation. These key principles are part of customary international law.

The Water Convention goes beyond customary international law by specifying and further developing these key obligations. For example, the principle of cooperation is further detailed through the Convention’s obligations to establish joint bodies for transboundary water cooperation, to hold consultations, to exchange information, to provide mutual assistance upon request, and so on. By acceding to the Convention, a country can benefit from this more elaborated framework of obligations and requirements.

Furthermore, the Water Convention provides added value to customary international law by providing an institutional framework and mechanisms, which assist Parties in developing and carrying out day-to-day transboundary cooperation. The institutional mechanism of the Water Convention is led by the Meeting of the Parties —its highest political authority—that meets every three years and adopts the programme of work for the next three-year period. It also establishes working or subsidiary bodies to support the implementation of the programme of work (e.g. the Working Group on Integrated Water Resources Management or the Task Force on Water and Climate ). By acceding to the Water Convention, a country can benefit from tools, advice and assistance provided by the Convention’s intergovernmental platform that are not available to it through customary international law.1.13 What is the relationship between the Water Convention and other multilateral environmental agreements?

While every multilateral environmental agreement (MEA) has its focus on a specific environmental issue (e.g. biodiversity or climate change) or tool (e.g. public participation or environmental assessment), many of them intervene on the management and protection of water resources. For this reason, the implementation of many MEAs supports the implementation of the Water Convention and vice versa, as shown by the following examples.

• Some World Heritage sites protected under the 1972 Convention concerning the Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage (World Heritage Convention) , especially those designated under natural or mixed criteria, contain transboundary waters and water-related ecosystems. The list of wetlands of international importance, designated as Ramsar sites under the 1971 Convention on Wetlands of International Importance especially as Waterfowl Habitat (Ramsar Convention) , includes many transboundary wetlands. The status of a World Heritage site or a Ramsar site often results in the designation of the respective sites and transboundary waters within these sites as protected areas, while simultaneously implying additional protection mechanisms through the frameworks of the World Heritage Convention or the Ramsar Convention, respectively. At the same time, cooperation on transboundary waters through specific transboundary water agreements and joint bodies, as required by the Water Convention, ensures for operational mechanisms and enables more effective protection of World Heritage Convention or Ramsar Convention sites when such sites include transboundary waters.

• The three Rio Conventions: the 1992 Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD), the 1994 United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification in those Countries Experiencing Serious Drought and/or Desertification, Particularly in Africa (UNCCD) , and the 1992 United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) are relevant for the sustainable management and protection of water resources, including in a transboundary context. The instruments developed under these conventions, such as the Aichi Biodiversity Targets and the National Biodiversity Strategies and Action Plans (NBSAPs) under the CBD, the Land Degradation Neutrality (LDN) Target Setting Programme under the UNCCD, and several of the Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) and National Adaptation Plans (NAPs) in the framework of the UNFCCC include measures to support IWRM and the protection of water-related ecosystems. In turn, the implementation of the Water Convention contributes to the implementation of the Rio Conventions, for example when joint bodies for transboundary water cooperation participate in the development and implementation of NBSAPs, climate change adaptation measures or NDCs.

• Implementation of the Water Convention can benefit from the implementation of the 1991 Convention on Environmental Impact Assessment in a Transboundary Context (Espoo Convention) that includes the procedures for conducting an environmental impact assessment (EIA), as well as the 1998 Convention on Access to Information, Public Participation in Decision-making and Access to Justice in Environmental Matters (Aarhus Convention) that provides for the requirements regarding access to information and public participation in decision-making. In turn, participation of joint bodies for transboundary water cooperation in EIA, which is among the tasks of joint bodies under the Water Convention, enhances the quality of a transboundary EIA. Public participation in the activities of joint bodies for transboundary water cooperation or the development of river basin management plans directly contributes to the implementation of the Aarhus Convention.

In addition to synergies in the normative frameworks and related implementation efforts by States Parties to respective instruments, there are also many examples of practical cooperation in the activities implemented under the auspices of the Water Convention and other MEAs. For example, cooperation with the Ramsar Convention secretariat in the preparation of the 2011 Second Assessment of Transboundary Rivers, Lakes and Groundwaters under the Water Convention made possible the assessment of 25 wetlands of transboundary importance, highlighting the need for stronger coherence between water management and conservation efforts at the transboundary level.

Further exploring the synergies between the Water Convention and other MEAs and relying on such synergies in national policies and at transboundary, regional and global levels may bring added value to implementation efforts by enabling countries to move towards a more integrated approach, inherent for the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development.

Additional resources:

• Boisson de Chazournes, Laurence, Christina Leb and Mara Tignino, The UNECE Water Convention and Multilateral Environmental Agreements. In: Tanzi, Atilla et al., eds. The UNECE Convention on the Protection and Use of Transboundary Watercourses and International Lakes: Its Contribution to International Water Cooperation. Leiden, NL: Brill | Nijhoff, 2015. pp. 60–72.

• Second Assessment of Transboundary Rivers, Lakes and Groundwaters (ECE/MP/WAT/33). - 2. GLOBAL APPLICATION

-

Accordion content 2.

- 3. RELATIONSHIP WITH THE 1997 WATERCOURSES CONVENTION

-

New accordion content

- 4. SCOPE

-

New accordion content

- 5. PRINCIPLES AND OBLIGATIONS

-

New accordion content

- 6. IMPLEMENTATION, OPERATION, CAPACITY AND COMPLIANCE

-

New accordion content

- 7. ACCESSION PREPARATION AND PROCESS

-

New accordion content

Did not find your question here? Contact us and we will be happy to reply.